artifacts and identity

sharonkuhow do artifacts such as songs, grocery stores, fishing tools, etc help Naluwan people claim their identities (cultural, professional, social, personal?)

how do artifacts such as songs, grocery stores, fishing tools, etc help Naluwan people claim their identities (cultural, professional, social, personal?)

There are manu artifacts mentioned in your fieldnote--songs, stories, fishing tools, grocery stores, etc. How do you analyze these artifacts--why and how were they constructed, used? What are the social, economic, cultural meanings/functions of these artifacts? And how have these artifacts helped construct the sense of place and identity of the Naluwan people?

There are missing data points within the dataset (attributed to non-reported information). This dataset has also been acknowledged to be limited in its prioritization of government data, which could have political limitations that may skew the degree of severity for disasters reported.

This dataset can be used to demonstrate the geographic distribution of disasters in Vietnam over time. This database recognizes multiple dimensions of disaster, including natural (typhoons, hurricanes), technological (a chemical spill, a factory explosion), and more

This dataset includes information at the country and regional level. Reports of disasters, both natural and human-related, are recorded at the country and province, region, or city level.

This resource has been used in a publication written by Hoang et al., 2018 on the economic cost of the Formosa Toxic Waste Disaster in Central Vietnam. It is specifically used within the journal article to highlight the forms in which disasters can take place within a nation, and the rising cases of industrial disasters that have afflicted vulnerable communities within the last decade. This characterization sets the stage and context for the Formosa disaster, and integrates it within a wider conversation about the effects of intensified industrialization on the environment.

These datasets all involve a strong spatial component. The presentation of such data could best be done via GIS Software, with their integration within a story map to demonstrate the importance of environmental stewardship to natural environments as well as the people who depend on such resources for their livelihoods. For example, EPI data can be incorporated with EM-DAT’s disaster data to better understand the relationship between a country’s EPI performance and the amount of technological disasters it observes. A country’s EPI score on Fish Stock Status can be compared with how much the nation’s GDP relies on fisheries to draw attention to discrepancies between stewardship and a country’s reliance on this resource. This process will require a user to be familiar with GIS Software and spatial plotting of data points (as the datasets themselves have not been integrated into ArcGIS), and using this software to integrate information together into meaningful maps.

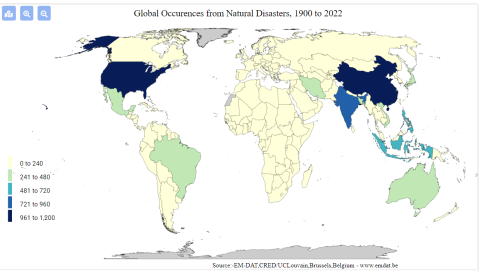

[Source: EM-DAT Public] This graphic shows the prevalence of technological disasters [includes toxic spills, industrial explosions, etc.] by country. This can be used to characterize, on a transnational level, where potential industrial harms are centralized or concentrated. While it does not characterize more insidious harms, such as air pollution, it can be a direct and easy to understand measure of environmental harm distribution across the globe.

Additionally, data is available as excel sheets, which allows users to produce their own graphics on the prevalence of disasters within a particular nation over a desired time interval.

This was developed in 1988 by personnel from the Center for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED) within the Université catholique de Louvain (UCLouvain) with funding from the Belgian government and the World Health Organization (WHO), this data source aims to provide free open access information for users affiliated with academic organizations, non-profits, and international public organizations looking to gain understanding on the distribution of disaster occurrences around the globe.

The EMT disaster database is compiled from a wide variety of sources, including UN agencies, NGOs, insurance companies, research institutes, and press agencies. The dataset compilation process prioritizes data from UN agencies, the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, and government agencies. Entries are reviewed prior to consolidation, and this process of checking and incorporating data is done on a daily basis. More routined data checking and management also occurs at a monthly interval, with revisions made at the end of each year.