main argument, narrative and effect

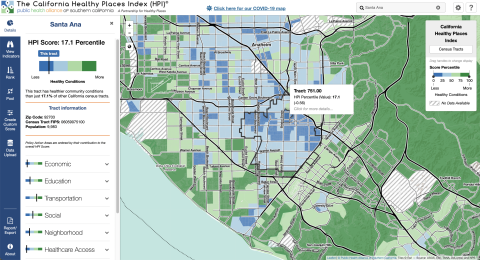

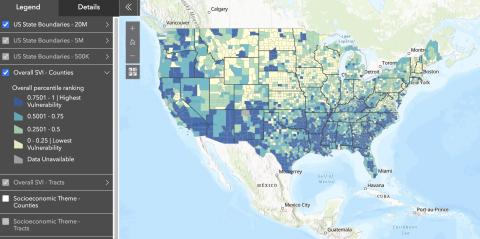

margauxfThe authors examine the practice of “hot spotting,” a form of surveillance and intervention through which health care systems in the US intensively direct health and social services towards high-cost patients. Health care hot spotting is seen as a way to improve population health while also reducing financial expenditures on healthcare for impoverished people. The authors argue that argue that ultimately hot spotting targets zones of racialized urban poverty—the same neighborhoods and individuals that have long been targeted by the police. These practices produce “a convergence of caring and punitive strategies of governance” (474). The boundaries between the spaces of healthcare and policing have shifted as a “financialized logic of governance has come to dominate both health and criminal justice” (474).