songs as artifacts

sharonku1. Songs as artifacts,

2. Faith in God enables their forgiveness: how does the belief in God and in Amis ancestor co-exist? (阿美人有祖靈概念嗎?)

3. 遷徙的過程: 從美山,新莊到新竹,從打漁到打零工,這一路轉換對阿嬤個人,她的家庭以及部落代表著什麼?以及這段小歷史如何被鑲嵌在大歷史的脈絡中?

1. Songs as artifacts,

2. Faith in God enables their forgiveness: how does the belief in God and in Amis ancestor co-exist? (阿美人有祖靈概念嗎?)

3. 遷徙的過程: 從美山,新莊到新竹,從打漁到打零工,這一路轉換對阿嬤個人,她的家庭以及部落代表著什麼?以及這段小歷史如何被鑲嵌在大歷史的脈絡中?

The SVI has been used to assess hazard mitigation plans in the southeastern US, evaluate social vulnerability in connection to obesity, explore the impact of climate change on human health, create case studies for community resilience policy, and even to look beyond disasters in examining a community’s physical fitness.

The SVI was also used by public health researchers to explore the association between vulnerability and covid-19 incidence in Louisiana Census Tracts. Previous research examining associations between the CDC SVI and early covid-19 incidence had mixed results at a county level, but Biggs et al.’s study found that all four CDC SVI sub-themes demonstrated association with covid-19 incidence (in the first six months of the pandemic). Census tracts with higher levels of social vulnerability experienced higher covid-19 incidence rates. Authors of this paper point to the long history of racial residential segregation in the United States as an important factor shaping vulnerability and covid-19 incidence along racialized lines, with primarily Black neighborhoods typically most disadvantaged relative to primarily white neighborhoods. The compounding factors shaping vulnerability along racialized lines—high rates of poverty, low household income, and lower educational attainment—are identified as shaping the likelihood of covid-19 infection. The authors encourage policy initiatives that not only mitigate covid-19 transmission through allocation of additional resources and planning, but that also “address the financial and emotional distress following the covid-19 epidemic among the most socially vulnerable populations” (Biggs et al., 2021).

Biggs, Erin N., Patrick M. Maloney, Ariane L. Rung, Edward S. Peters, and William T. Robinson. 2021. “The Relationship Between Social Vulnerability and COVID-19 Incidence Among Louisiana Census Tracts.” Frontiers in Public Health 8. https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpubh.2020.617976.

Lehnert, Erica Adams, Grete Wilt, Barry Flanagan, and Elaine Hallisey. 2020. “Spatial Exploration of the CDC’s Social Vulnerability Index and Heat-Related Health Outcomes in Georgia.” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 46 (June): 101517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101517.

The CDC SVI has been acknowledged to be limited in capturing accurate representations of small-area populations that experience rapid change between censuses (e.g. New Orleans in the years following Hurricane Katrina).

The Index is also limited, like other mapping tools, by the lack of homogeneity within any census tract or county/parish. There may very well be more vulnerable communities and individuals living in overall less vulnerable areas. Homeless populations may also specifically not be represented within studies that rely on geocoding by residential address. Length of residence within a geographic area may also impact results.

The index is also limited by calculations that account for where people live, but not necessarily where they work or play. The lives of individuals are not necessarily restricted to the boundaries of a census tract or county/parish.

Lastly, vulnerability is only one component of several components that are important for public health officials and policymakers to consider—the hazard itself, the vulnerability of physical infrastructure, and community assets and resources are other elements that must be taken into account for reducing the effects of a hazard.

This data resource has also been critiqued by Bakkensen et al. for not having been explicitly tested and empirically validated to demonstrate that the index performs well (a problem they identify as characterizing multiple indices).

Bakkensen, Laura A., Cate Fox-Lent, Laura K. Read, and Igor Linkov. 2017. “Validating Resilience and Vulnerability Indices in the Context of Natural Disasters.” Risk Analysis 37 (5): 982–1004. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.12677.

There is a national data set that ranks all counties or census tracts within the entire data set (useful for a multi-state analysis). The user also has the option to utilize a state data set, which ranks counties or census tracts only within the state selected.

The CDC/ATSDR SVI draws on the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (ACS), 5-year estimates. The most recently available SVI dataset is for 2018, which utilizes the ACS 2014-2018 data.

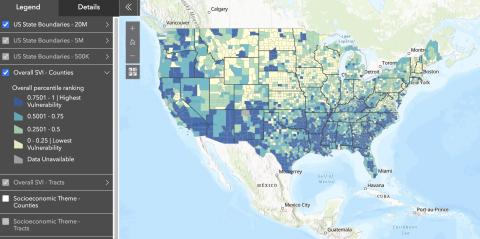

Users must select the ranking variable for either the overall vulnerability index score or for one of the four sub themes: Socioeconomic Status, Household Composition & Disability, Minority Status & Language, or Housing Type & Transportation.

A dictionary of terms used in this data resource are available at the bottom of this webpage: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/placeandhealth/svi/documentation/SVI_documentation_2018.html.

The CDC/ADSDR SVI is designed to help public health officials and local planners with preparing and responding to emergency events like hurricanes, disease outbreaks, or exposure to dangerous chemicals. The SVI databases and maps can be used to estimate the amount of supplies need (e.g. food, water, medicine, etc.), to identify areas in need of emergency shelters, to estimate the number of emergency personnel need, to create evacuation plans, and to “identify communities that will need continued support to recover following an emergency or natural disaster” (https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/placeandhealth/svi/fact_sheet/fact_sheet.html).

The SVI determines the social vulnerability of every census tract in the United States. The index ranks each tract on 15 factors grouped into four related themes (see below).

Each census tract/county has a percentile ranking that represents the proportion of tracts/counties for which the tract/county of interest is equal to or lower in terms of social vulnerability. Higher percentile ranking values indicate greater vulnerability. For instance, ranking of 0.85 indicates that the tract/county of interest is more vulnerable than 85% of tracts/counties but less vulnerable than 15% of tracts/counties.

The CDC defines social vulnerability as the extent to which certain social conditions might affect a community’s capacity to respond to a disaster and prevent human suffering and financial loss.

Starting in 2014, the CDC has also added a database for Puerto Rice, as well as for Tribal Census Tracts, which are defined independently of standard county-based tracts.

Overall Vulnerability

1. Socioeconomic Status

2. Household Composition and Disability

3. Minority Status and Language

4. Housing Type and Transportation

In 2018, two adjunct variables (not included in the overall SVI rankings) were added: 2014-2018 ACS estimates for persons without health insurance, and an estimate of daytime population taken from LandScan 2018.

This data is made available by the CDC Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) and more specifically the Geospatial Research, Analysis, and Services Program (GRASP), a team of public health and geospatial science, technology, visualization, and analysis experts. Their mission is to provide leadership, expertise, and education in the application of geography, geospatial science, and geographic information systems (GIS) for public health research and practice.

CDC/ATSDR Social Vulnerability Index

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/ Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry/ Geospatial Research, Analysis, and Services Program. CDC/ATSDR Social Vulnerability Index [Insert 2018, 2016, 2014, 2010, or 2000] Database [Insert US or State]. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/placeandhealth/svi/data_documentation_downloa…. Accessed on [Insert date].