Luísa Reis-Castro: mosquitoes, race, and class

LuisaReisCastroAs a researcher, I’m interested in the political, ecological, and cultural debates around mosquito-borne diseases and the solutions proposed to mitigate them.

When we received the task, my first impulse was to investigate about the contemporary effects of anthropogenic climate change in mosquito-borne diseases in New Orleans. But I was afraid to make the same mistake that I did in my PhD research. I wrote my PhD proposal while based in the US, more specifically in New England, during the Zika epidemic, and proposed to understand how scientists were studying ecological climate change and mosquitoes in Brazil. However, once I arrived in the country the political climate was a much more pressing issue, with the dismantling of health and scientific institutions.

Thus, after our meeting yesterday, and Jason Ludwig’s reminder that the theme of our Field Campus is the plantation, I decided to focus on how it related to mosquitoes in New Orleans.

The Aedes aegypti mosquito and the yellow fever virus it can transmit are imbricated in the violent histories of settler-colonialism and slavery that define the plantation economy. The mosquito and the virus arrived in the Americas in the same ships that brought enslaved peoples from Africa. The city of New Orleans had its first yellow fever epidemic in 1796, with frequent epidemics happening between 1817 and 1905. What caused New Orleans to be the “City of the Dead,” as Kristin Gupta has indicated, was yellow fever. However, as historian Urmi Engineer Willoughby points out, the slave trade cannot explain alone the spread and persistance of the disease in the region: "Alterations to the landscape, combined with demographic changes resulting from the rise of sugar production, slavery, and urban growth all contributed to the region’s development as a yellow fever zone." For example, sugar cultivation created ideal conditions for mosquito proliferation because of the extensive landscape alteration and ecological instabilities, including heavy deforestation and the construction of drainage ditches and canals.

Historian Kathryn Olivarius examines how for whites "acclimatization" to the disease played a role in hierarchies with “acclimated” (immune) people at the top and a great mass of “unacclimated” (non-immune) people and how for black enslaved people "who were embodied capital, immunity enhanced the value and safety of that capital for their white owners, strengthening the set of racialized assumptions about the black body bolstering racial slavery."

As I continue to think through these topics, I wonder how both the historical materialities of the plantation and the contemporary anthropogenic changes might be influencing mosquito-borne diseases in New Orleans nowadays? And more, how the regions’ histories of race and class might still be shaping the effects of these diseases and how debates about them are framed?

pece_annotation_1474844432

a_chenThey worked with a social ecology that is consider closely related to federal government, by control and prevent the issues can assist government boost the employment rate and further with economy boost.

pece_annotation_1475441872

a_chenThe film has not included the patient’s viewpoint or the locals’ viewpoints within this kind of situations. This might due to the communication difficulties with the language. If the audience viewed the content with locals’ viewpoint might benefit from knowing the cultural practices and plan for the future interaction more carefully.

pece_annotation_1477238733

a_chenFrom the search of app store on my phone, there is no app has similar function as Cloud9 does. Most of the apps just provide facts and general treatment to the user but not the interactions with parties like Cloud9 does.

pece_annotation_1473037714

a_chenUNSCEAR 2013 Report: The Fukushima Accident This report is published by The United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR). It is to evaluate and report the levels and the effects of exposure on the ionising radiation.

pece_annotation_1473038180

a_chenThis convention has instructed clear enough for the first responders (i.e. the involving states) to get into action with any possible nuclear hazards reporting. For the technical professionals, the main webpage of the convention documents has a related resources column that assist them to gain relevant information with emergency responses via updated visualized data etc.

pece_annotation_1473634132

a_chenThe program itself is mainly funded by Handicap-International and USAID. For the other projects related to Haiti’s aftermath reconstruction are supported by AFD, ECHO, UN etc.

pece_annotation_1474297484

a_chenThe product is designed in the way that the portable bridge can be expand from a folded mode to a bridge length takes up to across a river. It expanded in a scissor-like (90° turned scissor lift) action, then slides out the decks with end-to-end to provide platforms for vehicles.

This design is “Made of aluminum alloy and steel, it’s lightweight and easy to transport, yet sturdy enough for cars to cross.” [1]

pece_annotation_1475441743

a_chenThis study has let the news agencies to have a new term to report with the articles that relevant to public health and mass imprisonment when introducing contents to the general publics. The data and observations been made within the epidemiological study has assisted the new articles to explain the incarcerated group in a more colloquial and easy understanding way.

“When public health authorities talk about an epidemic, they are referring to a disease that can spread rapidly throughout a population, like the flu or tuberculosis.

But researchers are increasingly finding the term useful in understanding another destructive, and distinctly American, phenomenon — mass incarceration.” [http://www.nytimes.com/2014/11/27/opinion/mass-imprisonment-and-public-…]

“Since the 1970s, the correctional population in the US has ballooned by 700 percent. This phenomenon is often referred to as mass incarceration.” [http://www.philly.com/philly/blogs/public_health/Mass-Incarceration-A-P…]

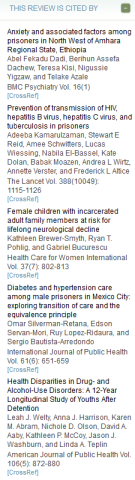

Professional uses citations: