Everyday life between chemistry and landfill: remaking the legacies of industrial modernity

Janine Hauer, M.A. (Researcher), Philipp Baum B.A. (Research assistant)

Janine Hauer, M.A. (Researcher), Philipp Baum B.A. (Research assistant)

As a participant in the NOLA Anthropocene Campus, I have gained insights on how communities, stewards, and managers of ecosystems in New Orleans have rolled out forms of interspecies care vis-à-vis ongoing environmental changes, coastal erosion, climate catastrophes and their deeply present and current effects (i.e., the 2010 BP oil disaster). Whilst much analytical lens has been given to geospatial changes in the study of the Anthropocene, here, I focus on how relations to non-human beings, also threatened by the changing tides of NOLA’s waterscapes, can enrich our understanding of such global transformations.

After disasters like Katrina, urban floodwaters harbored many hidden perils in the form of microbes that cause disease. Pathogenic bacterial exposure occurred when wastewater treatment plants and underground sewage got flooded, thus affecting the microbial landscape of New Orleans and increasing the potential of public health risks throughout Southern Louisiana. But one need not wait for a disaster event like Katrina to face these perils. Quotidian activities like decades of human waste and sewage pollution have contaminated public beaches now filled with lurking microbes. Even street puddle waters, such as those found on Bourbon Street, contain unsanitary bacteria level from years of close human exploitation of horses and inadequate drainage in 100-year old thoroughfares. More recently, microbial ecologies have also changed in the Gulf of Mexico due to the harnessing of energy resources like petroleum. Lush habitats for countless species are more and more in danger sounding the bells of extinction for the imperiled southern wild.

Human-alteration has severely damaged the wetland marshes and swamps that would have protected New Orleans from drowning in the water surge that Hurricane Katrina brought from the Gulf of Mexico. The latter is something that lifelong residents (i.e., indigenous coastal groups) of the Mississippi River Mouth have been pointing to for a long time. Over the past century, the river delta’s “natural” infrastructure has been altered by the leveeing of the Mississippi River. Consequently, much of the silt and sediments that would generally run south and deposit in the river mouth to refeed the delta get siphoned off earlier upstream by various irrigation systems.

While some actors see it as a futile effort, there have been many proposals to restore the Mississippi River Delta. For instance, the aerial planting of mangrove seeds has even been recommended to help protect the struggling marshes and Louisiana’s coastal region. Tierra Resources, a wetland’s restoration company, proposed that bombing Lousiana’s coast with mangrove seeds could save it. Mangrove root systems are especially useful in providing structures to trap sediments and provide habitats for countless species. Additionally, mangroves have been touted as highly efficient species in carbon sequestration, thus taking carbon dioxide out of the biosphere.

Species diffusion into new environments has been of great concern for the different lifeways these soggy localities sustain, whether human or non-human. Many so-called “invasive species” have been identified throughout the river delta by researchers at the Center for Bioenvironmental Research hosted by Tulane and Xavier University. Such species have disrupted local ecological relations and practices and have had profound economic effects. Some plants have even entirely blocked waterways in the swamps and estuaries where salt and freshwater mix.

Louisiana’s humid subtropical climate, and the diverse ecosystems therein, also warrant attention in that they can incubate some of the world’s deadliest parasites and other microbes. Of particular concern would be some of today's Neglected Tropical Diseases (i.e., Chagas, Cysticercosis, Dengue fever, Leishmaniasis, Schistosomiasis, Trachoma, Toxocariasis, and West Nile virus) often perceived as only affecting tropical regions of Latin America and revealing the enduring legacies of colonial health disparities.

How and when are seemingly quotidian events and upsets understood as not isolated but rather as produced in conjunction with other anthropocenics worldwide? What roles will interspecies relations and forms of care play as we cope with further anthropocenic agitation?

NOLA’s oldest tree, McDonogh Oak in City Park, 800 years old: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DK9YoGpng_c&t=0s

Other trees in New Orleans: https://www.atlasobscura.com/things-to-do/new-orleans-louisiana/trees

Due to the mass destruction of the area, the first few days’ data were not able to collect (not only the destruction, but the rescue was the first priority). Therefore, the scientific committee used models to simulate and analyse the data (might not be accurate on the early stage). After the rescue, many countries have provided data to assist the works. For the long‐live radioactive substances, the data was able to collect with the ground soils. Furthermore, prediction can be made with the pass experiences and the basic models.

The received data can be managed and visualised into charts or map tiles (e.g. open street maps or satellite maps). The data is visualized in the panel of “Visualize Your Story “with four modes of visual features.

“… the murders occurred where it all began — in the remote forests of southeast Guinea, where superstition overwhelms education and whispers of Ebola stoke fear and sometimes violence.”

“The increase in violence marks a new dark chapter in the fight against Ebola…”

Since the article reported that this is the fourth edition of the design, most of the problems are solved during the refurbishment of product. So there are not many problems with the design as they tested with the publics. But they plan to make the bridge “stronger, longer, lighter, more compact and quicker to set up”.

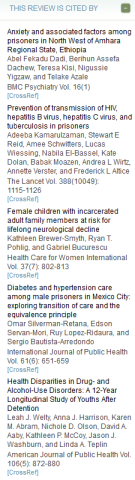

This study has let the news agencies to have a new term to report with the articles that relevant to public health and mass imprisonment when introducing contents to the general publics. The data and observations been made within the epidemiological study has assisted the new articles to explain the incarcerated group in a more colloquial and easy understanding way.

“When public health authorities talk about an epidemic, they are referring to a disease that can spread rapidly throughout a population, like the flu or tuberculosis.

But researchers are increasingly finding the term useful in understanding another destructive, and distinctly American, phenomenon — mass incarceration.” [http://www.nytimes.com/2014/11/27/opinion/mass-imprisonment-and-public-…]

“Since the 1970s, the correctional population in the US has ballooned by 700 percent. This phenomenon is often referred to as mass incarceration.” [http://www.philly.com/philly/blogs/public_health/Mass-Incarceration-A-P…]

Professional uses citations:

From the links provided within the article, relevant information about Hurricane Katrina can be viewed with the commentary and archival articles that published in The New York Times that written by other authors.

Also the author has made in contact with Memorial Medical Center in Uptown New Orleans to focus on the investigation into the detail situations happened with the floodwaters. Afterwards, gained more information on the lethal injection issues.

[http://www.nytimes.com/topic/subject/hurricane-katrina?inline=nyt-class…]

[http://www.nytimes.com/topic/subject/hurricanes-and-tropical-storms-hur…]

This policy is drafted by United State Environmental Protection Agency. And their mission is to protect human health and the environment via the development and enforcement with regulations.